When we subscribe, the operator sometimes provides a terminal, but it especially provides a communication service in the form of a SIM card.

For the terminal to function correctly on the network, the SIM card must be present. It is obviously necessary to identify each SIM card, or each subscription, in a unique way.

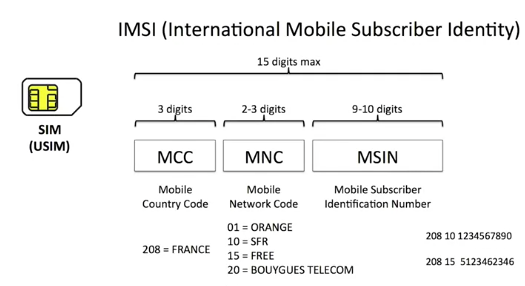

This is done using an identity called the International Mobile Subscriber Identity.

To ensure that two random subscribers, in the entire world, never have the same IMSI, the structure is hierarchical.

It starts with three digits indicating the MCC code – Mobile Country Code – the country where the user has subscribed, which is generally where he lives.

After that is the MNC – Mobile Network Code – which is the code of the network in the country, then a number allocated by the operator.

Two subscribers of the same operator never have the same number. The result is an identity of 15 digits maximum which is unique throughout the world.

The beginning of the IMSI therefore indicates to which country and operator the subscriber belongs. For example, the MCC for France is 208 and 10 is the code for SFR.

Here are two examples of IMSIs from 2 subscribers with different French operators. The IMSI of a subscriber never changes, unless he changes unless he changes operators, of course. It is used when you move through the network.

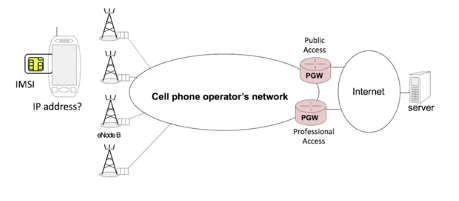

A 4G network enables the terminal to connect to the Internet. All equipment connected to the internet must have an IP address to be able to send and receive data. In most cases, the IP address is not allocated statically. It is allocated at power-up, during a process called “attachment".

An operator can provide various types of services. For example, a public access or a professional access.

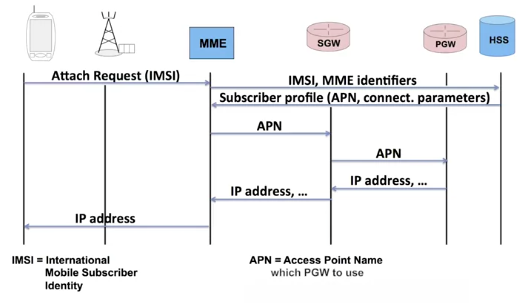

During the attachment procedure, the terminal indicates the type of service it wants, notably by specifying the APN, the Access Point Name, which indicates to the network which P-Gateway to use. Let’s look at a very simple example of how attachment works.

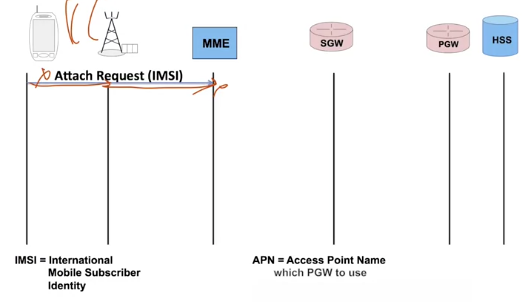

When I turn on my terminal, it reads the SIM card to know the country code and the name of my operator. We’ll assume that I’m in the country where I subscribed. The terminal searches my operator’s network, listening to the beacon channels of the surrounding systems.

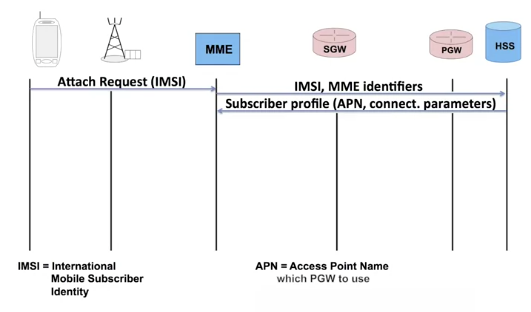

The operator’s code is transmitted on each beacon channel. As soon as it finds the right network, it sends an Attach Request message containing its IMSI. The message is received by the eNodeB, transmitted to the MME. The MME checks if it has the subscriber’s profile in its database. That’s not the case here, because we’re assuming that this is the first time I’ve turned my terminal on.

The MME will then verify with the HSS if the subscriber is known and has access to the network. The HSS searches for the subscriber and transfers his profile, as we saw during the first week. The message includes the APN, Access Point Name.

Once the MME has stored the profile, it informs the HSS. We still haven’t spoken about an IP address. An IP address is linked to a location. In this case, the IP address is linked to the P-Gateway.

The choice was made by the designers of 4G networks, on one hand to allow dynamic address allocation and, on the other, to leave this allocation up to the P-Gateway.

The MME sends a message to the S-Gateway which it resends to the P-Gateway. The P-Gateway can allocate an IP address. This IP address is then sent from the P-Gateway to the S-Gateway, then from the S-Gateway to the MME to finally arrive at the mobile terminal. From the moment the terminal has an IP address, it can work.

What are the possible problems?

Let’s imagine that I tamper with my terminal so that it sends the IMSI of my neighbor.

The Principle Security Mechanism

- Fraudulent use of the network -> Authentication

- Listening to exchanges -> Encryption

- Modifying messages -> Integrity

- Tracking/location of the terminal -> Temporary identity

I could use the network at his expense: The network must verify that, when a terminal accesses a network, it corresponds to a valid subscription, to an SIM card actually issued by the operator. This is the authentication mechanism.

With a receiver set to the frequency of the base station, it is very easy to listen to what it transmits. A person with malicious intent could learn the information transmitted to me. This must be prevented. This is enabled by the encryption mechanism.

An attacker with a transceiver can very easily change the IP address that was allocated to me during the attachment procedure by superposing a signal on the one transmitted by the base station.

To prevent this, a mechanism was developed that enables the recipient of a message to control the integrity of this message.

When a terminal activates a service, it must identify itself. By default, the identifier used is the IMSI.

If an attacker listens to the exchanges on the radio band and detects an IMSI, it knows which subscriber is nearby.

Therefore, we avoid transmitting the IMSI. Instead, we use a temporary identity which is regularly renewed. Authentication, encryption, integrity, allocation of a temporary identity are the mechanisms which we’ll see in this week’s videos. This will bring us to look again at the attachment procedure, looking at how the security mechanisms are implemented.